This is the forth part in the article series The Performing Organization. The series will explore and explain the organizational characteristics that Agile practices try to unlock. There will be Agile principles and practices mentioned, but they will not be the focus. Focus will be on overarching organizational capabilities that are common traits for well performing, efficient organizations. We will explore these capabilities by asking ourselves a number of fairly simple questions.

This article will be a double whammy, as we will ask two questions at the same time. Namely:

- How do we find out about problems?

- How do we react to problems?

The reason for asking these questions is to find out how quickly we can respond to unforeseen events, but also to highlight potential cultural issues that we may need to address.

So. How do we find out about problems?

Don’t want to know

As mentioned in the previous article, if we fear how bad news will be received, we might be inclined to hide the information—we don’t want to tell. However, there is also the scenario where we don’t want to know about the problem as a way to avoid responsibility.

This behavior might be in response to the culture of the organization, if the focus lies more on blame and accountability than finding solutions. Some companies try to fix badly designed organizations by “clarifying responsibility and accountability”, in an attempt to make things move faster. This is usually a deceptive practice, where cheer force becomes the modus operandi. If we fail to meet expectations, we will be put under scrutiny and pressure, so we avoid signaling problems for as long as we can.

Unwillingness to know about problems may also be a sign of overworked leadership, who are simply too swamped to take in any bad news. “Don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions”, might be the default response. While this can sound like a solution oriented attitude, it is likely to be an indication that lower level managers don’t have the mandate or trust to actually act on problems. If they solve the problem in a way that upper management does not approve of, there might be other repercussions.

A damned if you do, damned if you don’t kind of situation. This can cause decision paralysis in the ranks, where the safest bet is to turn a blind eye and do nothing.

Yearly survey

Companies that rely on the yearly employee survey as their main means to find out about problems are unlikely to turn the results into positive change. If we don’t continuously gather feedback, we probably don’t have an established way of working to habitually improve things. We are untrained in how to act or lack an established process to handle it. It’s not something we have in our collective toolbox.

Even if we do have a way of addressing these problems, we only gather feedback once per year, meaning we have a very slow response time. This will, in the best scenario, lead to minor improvements in one or two areas, but will not lead to any major shifts or significant positive change.

Our intentions may be in the right place, but our response capability is far too slow.

Regular review, but unclear outcome

A more constructive attitude is to regularly review the current situation. To speak Agile, this would be our recurring retrospectives.

This is a good practice, but what I often see, in my work in teams and organizations, is an inability to turn insights into actions. We are very aware of and open about the challenges we have, but we struggle to turn these realizations into actionable steps to improvement.

There are several reasons for this, but three common ones are:

A “not my job” attitude. That we perceive it as someone else’s job to fix the problem.

A lack of (or perceived lack of) autonomy to solve the problem. That we see the problem as being outside our sphere of influence, so we can’t take action.

A lack of established ways of working with improvement. That we are unaccustomed to taking charge and solving shared—or even our own—problems.

If it’s one of the first two reasons, we need a cultural shift to be able to better respond to problems. We might need to dig a little deeper to understand why people shirk responsibility or what we can do to increase the sense of autonomy in our teams.

If it’s the last reason, we are in pretty good shape to take further steps to improve.

Continuous evaluation with clear actions

I want to make a clear distinction between “review” and “evaluation”, because I often find organizations get stuck in review but unable to evaluate. A review is merely a listing of problems, an evaluation is an analysis and prioritization of that list, to find which areas we address first.

This is an important distinction that goes hand in hand with the ability to act on the problem.

For this to become second nature, we need to view this as a habit and not a process. The reason for this is that we want to reach a culture of addressing problems and making improvements. Everything that we need to do but don’t do habitually, we try to catch in our processes.

Solving problems needs to be in our culture—it needs to be habitual. It should be something that we just do! That’s what we should strive for. But to get there, we might need to start with having a process or way of working in place, to learn the new habit. Just make sure to make it lightweight. It needs to be easy to do the right thing!

Summary

Our ability to react to problems is by and large decided by our feedback cycles—how quickly we find out about them. But the likelihood of us even finding out is also affected by how we react to problems.

How do we react to problems?

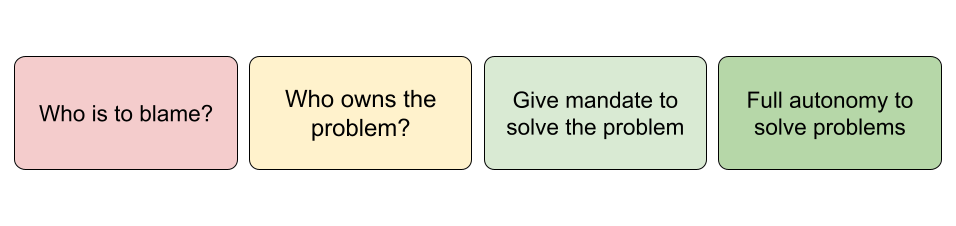

If the focus lies on blame, we may find ourselves in the situation where people don’t want to tell. I don’t encounter this behavior very often, because I think most leaders understand that if their employees fear telling them things, they will be in the dark and unable to govern.

What I do see far too often though, is a focus on finding out “who owns the problem”. When responsibilities fall between chairs, or spans several organizational units, there is usually a need for debate and negotiation on who should solve it. It’s not uncommon for this to lead to conflict and resistance. Especially if there are conflicting priorities and KPIs.

If my KPI will be negatively impacted because I need to spend resources on solving a problem for someone else, I may (understandably) be reluctant to oblige.

If this is the case, we need a way to quickly give mandate and priority to solving the issue. We would also do well in evaluating our KPIs, because we are probably sub-optimizing in a harmful way.

In the best of worlds, we have full autonomy in our teams to take responsibility for their problems. This is of course not always possible in every case, but we still need to be equipped to respond quickly, with decentralized decision making wherever possible.

So now that we have found out about the problem and we know what to do about it, how adaptable are we to change?

This leads us to the next, and last question of this series: How do we respond to a need for change?

Stay tuned for the next update!